Disclaimer: This article is more than 8 years old, and may not include the most up-to-date information or statistics. Please verify information with more recent sources as needed, and if you have any questions contact our Press Office.

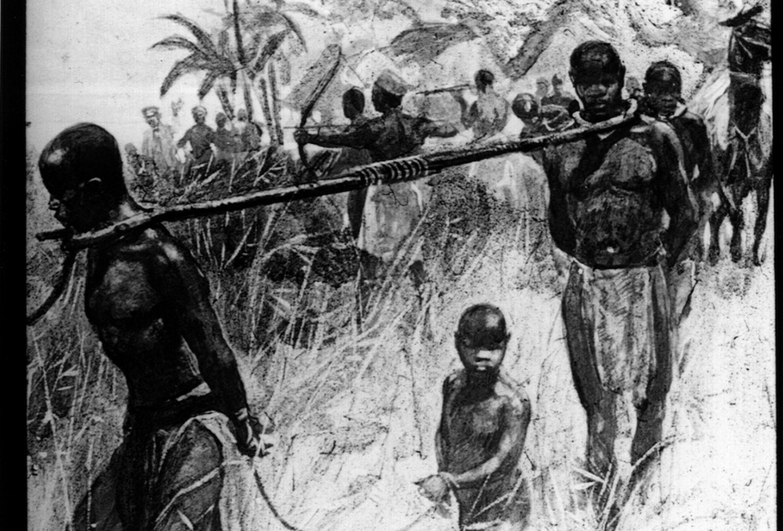

Historian Richard Huzzey explains how linking abolitionist efforts to the development agenda has brought mixed results.

11 February 2016

The link between development and the work to eradicate slavery has run throughout the organisation’s history, right back to its foundation as the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society (Anti-Slavery International’s predecessor) in 1839 and to generations of abolitionists before that.

Olaudah Equiano, the former slave who published the “Interesting Narrative” of his life in 1789, argued that Britons had more to gain by trading with free Africans than dealing in slaves.

Thomas Clarkson – whose name is given to Anti-Slavery International’s current offices – assembled a travelling case of sample spices, dyes, and goods from agricultural production that Africans would be able to export, once the raids of slave traders had been extinguished.

Equiano and Thomas’s brother John Clarkson played leading roles in the abolitionist experiment to establish a colony of free Africans in Sierra Leone. The plan was to spread the knowledge and example of the benefits of commercial agriculture as an antidote to slave trading.

However, the strict discipline of labour in Sierra Leone foreshadowed the coercive, superior attitude that abolitionists often showed towards less developed societies. Equiano quit the mission before it left England, out of frustration at his marginal, token role.

By the 1840s, following emancipation in Britain’s colonies, campaigners remained interested in tying development and abolition. They gradually realised that British trade with West Africa was not the easy antidote some had hoped as it remained intertwined with the continuing slave trade to the Americas.

However, in the second half of the century the Society started to work with the Aborigines’ Protection Society to prevent forced labour of colonised peoples in British territory across the world.

Yet, while vigilant against British slave ownership, abolitionists tended to go along with government’s policies tolerating “traditional” forms of forced labour within African societies – it was the evil of slavery of “higher” over “lower” races that they opposed.

Racist ideas about a civilising mission became bound up with anti-slavery development. The League of Nations and later the United Nations started with definitions of slavery drawn up by Lord Lugard, governor of British Nigeria, who distinguished between “traditional” practices for the natural development of colonies and the higher standards expected for the “civilised” world.

Historian Tony Hopkins has persuasively suggested that the post-slave-trade development in Africa constituted the world’s first (of many) development plans for the continent. However, toleration of forced labour and imperial conquest sat comfortably alongside abolitionism and development plans.

Today, Anti-Slavery International is working alongside activists in the developing world rather than dictating to them. The efforts to eradicate slavery remain intimately tied to developing wealth for the poorest communities in the world; poverty and slavery have always bred together, and legal emancipation without agency and independence allows new forms of forced labour to re-emerge.

Article taken from our most recent issue of the Reporter magazine. To receive a paper copy of the Reporter by post please contact supporter@antislavery.org

All of our members receive the Reporter automatically twice a year, sign up here to become a member.