Disclaimer: This article is more than 5 years old, and may not include the most up-to-date information or statistics. Please verify information with more recent sources as needed, and if you have any questions contact our Press Office.

Report: EU Governments ‘pass the buck’ for protecting thousands of Vietnamese children trafficked through Europe.

7 March 2019

Thousands of children trafficked from Vietnam to the UK are suffering horrendous exploitation and abuse in transit through Europe as different governments pass the buck on protecting them, according to new research by Anti-Slavery International, ECPAT UK and Pacific Links Foundation.

The report, Precarious Journeys: Mapping Vulnerabilities of Victims of Trafficking from Vietnam to Europe, traces the journeys made by Vietnamese children and adults to the UK, finding that the governments of countries on key trafficking routes routinely fail to protect vulnerable Vietnamese children from exploitation.

Instead, governments’ rhetoric and policies around migration has led to ‘transit countries’ – countries comprising a temporary part of the route from Vietnam to the UK – to view trafficked Vietnamese children as the responsibility of other States.

This leaves exploited children unidentified as victims, unable to access protection from their traffickers and easy targets for further exploitation and harm.

Lack of safe, legal routes

Official figures show hundreds of Vietnamese children are trafficked from Vietnam to the UK each year[1], however it is widely accepted that the actual number of victims is likely to be significantly higher. In the UK, Vietnamese nationals are consistently within the top three nationalities of those identified as potential victims of trafficking, via the National Referral Mechanism (NRM) – the figures from 2009-2018 show 3,187 Vietnamese adults and children victims were referred into the NRM.[2]

Factors such as poverty, lack of political freedoms, and environmental disasters and climate change – combined with a lack of safe, legal migration routes – make children vulnerable to deceit by traffickers and risky job offers abroad.

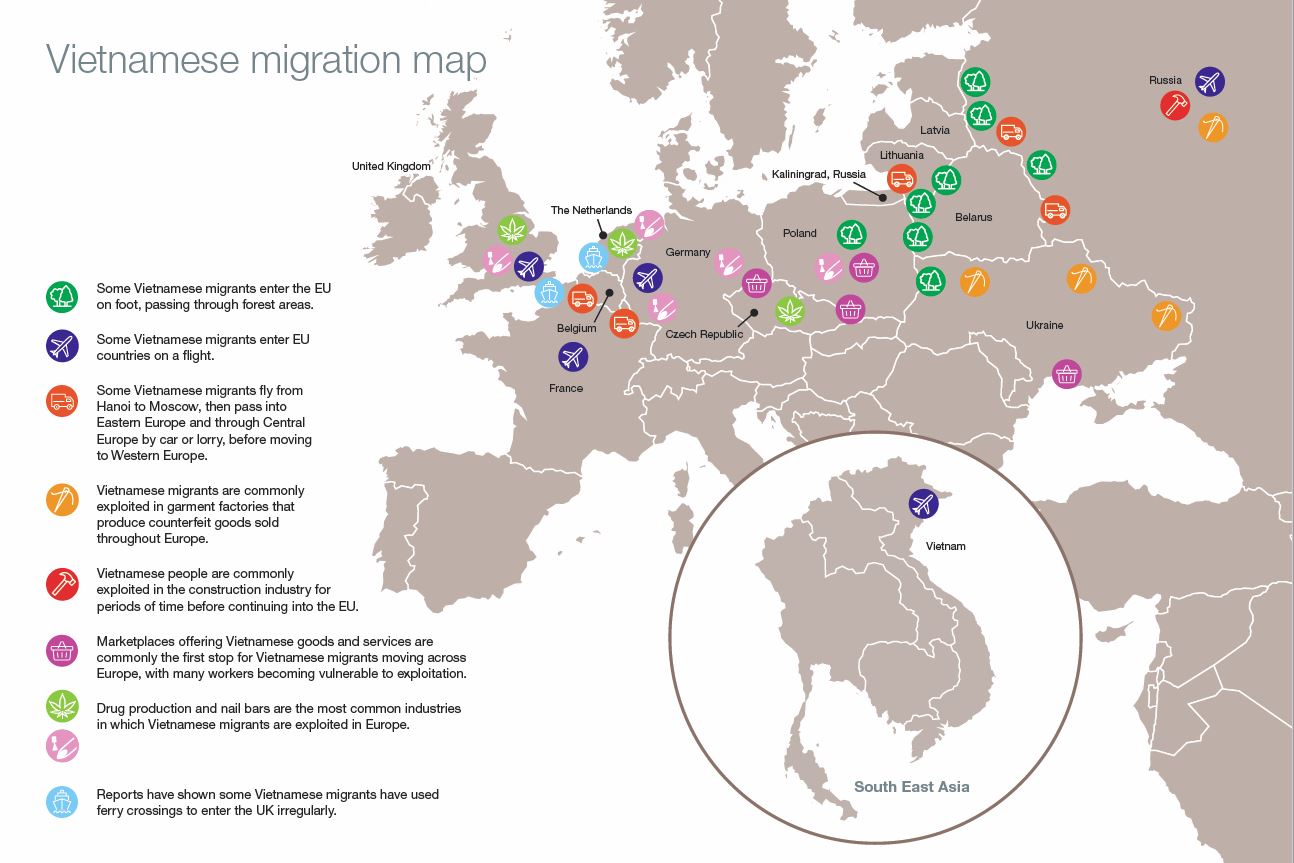

A typical journey takes children from Vietnam to Russia by plane, and then overland through Belarus, Ukraine, Poland, Czech Republic, Germany, the Netherlands and France. However, the report also highlights an emerging trend of transit from Vietnam to Europe via South America.

At each stage of the journey, children are vulnerable to exploitation in many forms and industries, including drug production, nail bars and manufacturing of counterfeit goods; as well as other forms of labour and sexual exploitation.

Children are typically controlled by debt owed to their traffickers for the cost of their travel out of Vietnam and the arrangement of a good job. However, these jobs frequently do not materialise, and instead children are forced to work in exploitative conditions to ‘pay back’ the debt, which grows each day. Additionally, children are controlled with use of violence as well as threats to themselves and their families back home.

Invisible and unprotected

Widespread low awareness and training in child trafficking across multiple European authorities in Poland, Czech Republic, Germany and the Netherlands and the UK means children are not being identified and protected, instead slipping through the net.

The research highlights a concerning number of children are repeatedly going missing from state care and being re-trafficked – often by the same networks of traffickers controlling them. Growing up with a fear of authorities prevents children from engaging with support services in Europe and further increases their risk of re-trafficking.

Once identified, children are fearful of returning to Vietnam. Travelling through irregular means, being forced to commit crime and owing a huge debt can mean that children will face reprisals from both their traffickers and Vietnamese authorities if they are returned to Vietnam.

“In France, the police didn’t help me and my traffickers found me again. When in the UK, I was treated like a criminal. One thing I would say to the people in Europe is, if it happened to your children, you wouldn’t ignore it.”

Debbie Beadle, Director of Programmes at ECPAT UK, said

”Under international law, States have a duty to protect children from trafficking and exploitation. It’s simply not acceptable for States to regard trafficked Vietnamese children as another country’s problem.

“Every professional who comes into contact with children across Europe should be able to identify victims and protect children from harm. Each country has a responsibility to ensure their frontline staff are trained, equipped and adequately resourced to protect children from trafficking.”

Jasmine O’Connor, CEO of Anti-Slavery International, said

“The extent of abuse children trafficked from Vietnam to Europe suffer is shocking. By the time they arrive in the UK, the vast majority have been mercilessly exploited along the way.

“We have to stop putting our heads in the sand and address this problem head on, together with other European and non-European countries.”

Dung, a Vietnamese member of ECPAT UK’s youth group for victims of trafficking, said

“I was a child who was taken across Europe by people I was scared of. In France, the police didn’t help me and my traffickers found me again. When in the UK, I was treated like a criminal. One thing I would say to the people in Europe is, if it happened to your children, you wouldn’t ignore it. One thing I would say to the UK Government is, why are the victims the ones you treat like criminals?”

Story of Dung*

Dung is from the North of Vietnam. She grew up with her grandparents, never knowing her real parents. Her family were poor and Dung didn’t attend school, instead helping her grandparents collect and sort recycling to earn an income. Her grandparents died when she was 14, leaving her alone with no caregiver. Dung survived by finding work in restaurants, where she would be given food in return for work. Initially, she was too upset to go back to the house she had shared with her grandparents, so she stayed in the restaurant. When she returned to the house after a couple of months, there was a man living there. He said he now owned the house. Dung asked the neighbours for help but no one would help her.

Dung went back to the restaurant she had worked and stayed in. The owners didn’t pay her or give her much food. They also beat her. It was in this restaurant that two women who were regular customers befriended Dung. They said they felt sorry for her and understood her pain as they had also had a hard life. They offered to cook her dinner one night, but after eating, Dung started to feel dizzy. She woke up in a house and was told she was in China. There were other women there and they were crying. Chinese men were watching over them and they had knives. Dung was not allowed to talk to any of the other women.

After a few days, Dung was forced to go on a journey. She didn’t know where she was going or why, and was terrified. Over a few weeks, she was driven across Europe in the back of different lorries. They stopped the journey from time to time, but Dung was never aware of which country she was in. After about a month of travelling, the lorry was stopped by police in France. The police took Dung’s finger prints and photo. Dung wanted to tell them what had happened to her, but there was no translator and she was scared. The men had said that they would kill her if she spoke. She was transferred to another police station, where she thought they were helping her, but instead they walked her through a door and she realised that she was being released. When she went outside there was a car waiting for her. Men pulled her into the car. She then was put on another lorry travelling to the UK. In the UK, Dung was kept in a house with other women and forced into sexual exploitation. She was told that she had to earn back the money that was paid to bring her to the UK.

*Not her real name

Precarious Journeys: Mapping vulnerabilities of victims of trafficking from Vietnam to Europe – read the summary report in PDF format:

Read the full report: (2.7MB) Precarious Journeys – full report.

Notes to editors:

The full report is expected to be released at the end of March. Debbie Beadle, Director of Programmes at ECPAT UK, and Jasmine O’Connor, CEO of Anti-Slavery International, are available for media interviews.

About ECPAT UK

ECPAT UK is a leading children’s rights organisation campaigning to protect children from trafficking and transnational exploitation. We support children everywhere to uphold their rights and to live a life free from abuse and exploitation. ECPAT UK has a long history of campaigning, having produced the first research into child trafficking in the UK in 2001 and advocating for changes in policy and legislation to improve the response of the UK Government and its international counterparts to such abuse. We also work directly with young victims of trafficking, whose experiences and voices inform all areas of our work. ECPAT UK is part of the ECPAT International network, which is present in 95 countries, working to end child exploitation. Find out more: www.ecpat.org.uk

About Anti-Slavery International

Anti-Slavery International, founded in 1839, is committed to eliminating all forms of slavery throughout the world. Slavery, servitude and forced labour are violations of individual freedoms, which deny millions of people their basic dignity and fundamental human rights. Anti-Slavery International works to end these abuses by exposing current cases of slavery, campaigning for its eradication, supporting the initiatives of local organisations to release people, and pressing for more effective implementation of international laws against slavery. For further information see: www.antislavery.org

Press contacts

- Sinead Geoghegan, Media and Communications Manager, ECPAT UK: 0203 903 4630, s.geoghegan@ecpat.org.uk

- Andy Wasley, Communications Manager, Anti-Slavery International: 0207 501 8934, a.wasley@antislavery.org