Disclaimer: This article is more than 6 years old, and may not include the most up-to-date information or statistics. Please verify information with more recent sources as needed, and if you have any questions contact our Press Office.

Guest blog by Christine Beddoe: By closing the Dubs scheme, the Government has left unaccompanied children at the mercy of traffickers.

31 July 2017

In March 2016 the Government passed the so-called Dubs Scheme to bring to the UK unaccompanied children travelling alone in Europe after fleeing war and hostilities in their own countries, many of whom at risk of trafficking.

But by February 2017 the Home Office abruptly curtailed the scheme after only 200 children had been brought to the UK. Parliament was told that the cap on numbers was set at 350, far lower than the 3,000 that had been previously discussed in parliament.

In a statement to the Parliament the Home Secretary announced that the Dubs scheme was being limited because it acted as a ‘pull factor’ for traffickers, but offered no evidence to support this position.

Contrary to this claim the All Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on Modern Slavery had been advised by NGOs monitoring the situation that the withdrawal of the scheme had left unaccompanied children completely stranded and with no-one to turn to but traffickers already operating in Europe and dozens of children had already gone missing.

The APPG committed to undertaking a fact finding Inquiry, but the General Election called soon after meant it was dissolved until the next parliament. Rather than delay any further, the Human Trafficking Foundation stepped in and agreed to sponsor an Independent Inquiry to be co-chaired by APPG’s Co-Chairs Fiona Mactaggart and Baroness Butler-Sloss supported by a small team in order to gather evidence from those working in the UK and in Europe with the most vulnerable children.

This was a deliberately rapid Inquiry. The situation for unaccompanied children can deteriorate fast without any safeguards in place, as we found out in April this year when a fire at the La Liniere migrant camp in Dunkirk razed the camp to the ground and hundreds of children went missing.

The Inquiry was appalled to hear the child protection crisis in Northern France due to the official policy of ‘no tolerance’ towards migrants and the escalation of riot police violence towards children in Calais with the routine use of CS (tear gas) and pepper spray on children and on their clothes and sleeping bags.

Evidence came forward of unaccompanied children forced into situations of sex for survival and having to witness the most brutal violence in uncontrolled encampments, or being sleep deprived through being made to move on from rough sleeping in the woods, having their sleeping bags pepper sprayed so they can’t use them but given nowhere safe to go.

The situation in Italy and Greece is chaotic, poorly monitored and underfunded, leaving children stranded, with no hope and so desperate to be re-united with friends and family in the UK that they are risking their life to get here.

The Inquiry recommended an immediate expansion of the Dubs scheme to address the crisis in France, Italy and Greece. Unfortunately to date the Government response has been quite pathetic and offered no concession, insisting that work is still on-going to identify children.

This has a very hollow ring to it when the small number of NGOs operating in the field already know the children that would benefit. Many children have been waiting over six months, some much longer, to be re-united with family in the UK. They live in precarious and dangerous situations.

The Inquiry found no evidence whatsoever that by creating a safe and legal route to safety in the UK you create a ‘pull factor’ for traffickers targeting vulnerable unaccompanied children. In fact it found the opposite, that by closing off such routes it feeds the trafficking and smuggling networks. The prices to get to the UK illegally go up, forcing children into situations where they are exposed to labour exploitation, sexual exploitation, criminal exploitation or a combination of all three.

A simple truth coming out of the Inquiry is that instead of protecting children who have fled to Europe for safety, Government is failing them, leaving the way open for smugglers and traffickers to exploit them.

If the Government truly has the interest of vulnerable children at heart it should remove the current cap from the Dubs scheme, widen its remit and mobilise staff to work collaboratively with NGOs so that more children can be offered immediate protection.

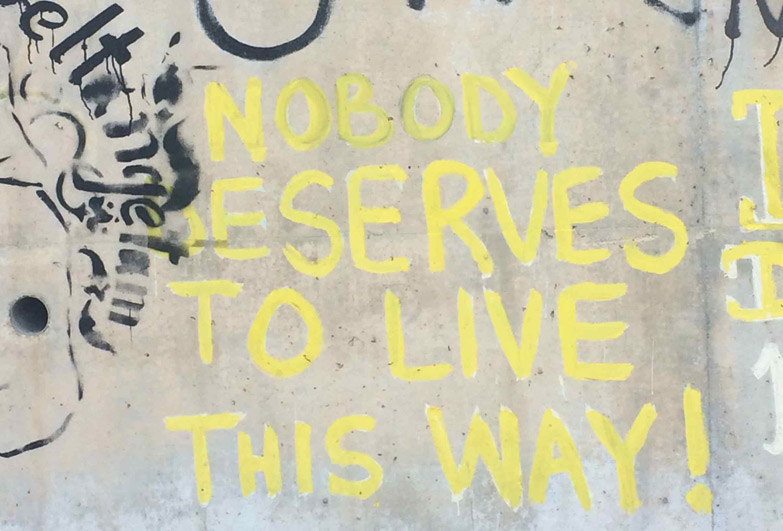

- Christine Beddoe is the author and inquiry advisor for The Human Trafficking Foundation report ‘Nobody deserves to live this way. An independent inquiry into the situation of separated and unaccompanied minors in parts of Europe‘.

- The Human Trafficking Foundation (HTF) is a UK-based charity which grew out of the work of the All Party Parliamentary Group on Human Trafficking in order to support the work of the many charities and agencies operating to combat human trafficking in the UK.