Disclaimer: This article is more than 8 years old, and may not include the most up-to-date information or statistics. Please verify information with more recent sources as needed, and if you have any questions contact our Press Office.

20 October 2015

Fasika Sorssa, a former migrant domestic worker in Lebanon tells how her employer kept her locked in the house for three years.

I grew up in Ethiopia. My father died when I was five and my mother was barely earning any money so I wanted to support her and my two younger brothers.

I had a neighbour who always had photos showing her great things, and she would tell me she had bought them thanks to her work in Lebanon. So I listened to stories about better life and wanted to go myself. I was sixteen.

My mum always said – don’t leave me. But I pushed her to allow me to go. An agent found me a job as a nanny to look after two children in Lebanon.

When I got there, I was impressed at first. The house was big and very nice. But after few days I realised it wasn’t the good life I came for. It was completely the opposite.

There were eight people in the family and I had to look after them. I had to clean, cook and look after two young grandchildren of my employer.

Very soon I found myself working eighteen hours a day, seven days a week, without any rest. I worked like a slave and was treated like one.

They beat me regularly. I was very tired so things could go wrong, but then they would beat me up for that.

The son of Madame tried to rape me several times.

I wasn’t allowed to call my mum or anyone. Madame said that I could write a letter to her, so I did write to my mum every month, but she never sent the letters. My mother thought I was dead.

They always kept me locked in the flat – I was locked in from the outside so that I couldn’t leave. I couldn’t go out for three years! Three whole years without going outdoors, without seeing the sun.

I was trying to escape but I was stuck on the 13th floor of a tall building. There was no way out.

The only times that I left the house was when I finished cleaning early, then I would be taken to the house of Madame’s older sister to clean her house. But I would be brought straight back and always kept under lock. I never met anyone.

The worst thing was that they didn’t even treat me like a human being. They would always put me down because of the colour of my skin and my culture. They would say: ‘Look at us, we are better. You’re not the same as us. Blame God for that that you’re worse than us.’ They would even forbid me from washing because they thought I didn’t need it.

I kept praying. But I stopped believing I would ever get back. Madame would say: “We can kill you and put you in the box, who will care?”

After two years, my contract ended and I wanted to go home but she said – one more year.

I wanted to kill myself. I was so tired and depressed that I couldn’t work normally. Finally Madame allowed me to go home to see my family and finally paid me for three years of work, after making me swear to God that I come back.

When I was on the plane people were asking me: “What’s wrong with you”? I was exhausted and wearing really bad clothes.

When my mum saw me, she couldn’t believe it. I was saying “I came, it’s me!” but she couldn’t believe it . She had been waiting to hear that I died.

The truth is, everything was exactly as she had warned me it would be. But my only dream was to support her. I just wanted to work. The recruiting agent who sent me there never checked anything, and never checked on me after I went to Lebanon. It felt like being sold.

When back in Ethiopia it was strange because people weren’t taking what I was telling them seriously. You could tell them it was very bad but they’d say “Why stay for three years?”. They wouldn’t believe I was locked in the house. I’d say, “She treated me very badly.” But they’d say “But you’re back!”

I am free now, I can do what I want. But it wasn’t like that in Lebanon. I had to fight to survive each day. Now I just hope that people read about my story and understand.

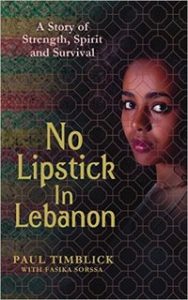

Fasika, together with her husband Paul Timblick wrote a book based on her experiences entitled ‘No Lipstick in Lebanon’. You can buy in it hardback here.

Interview by Jakub Sobik, Press and Digital Media Officer.