Disclaimer: This article is more than 4 years old, and may not include the most up-to-date information or statistics. Please verify information with more recent sources as needed, and if you have any questions contact our Press Office.

Focus on 1619 whitens and Europeanises the history of North America, argues Anti-Slavery patron historian Benjamin Lawrance

12 December 2019

For many in the USA, 2019 is a momentous anniversary, insofar as it has been commemorated as marking the 400 anniversary of slavery and a slave-based economy. In 1619, “20 and odd Negroes” arrived off the coast of Virginia, where they were “bought” by English colonists in Jamestown.

These captive Africans are often cited as the first enslaved people in the United States. While this was no doubt a momentous moment for Virginia, and a horrific experience for the men and women in question, unfortunately, this is an oversimplification and overlooks the long history of slavery and colonialism in the Western hemisphere.

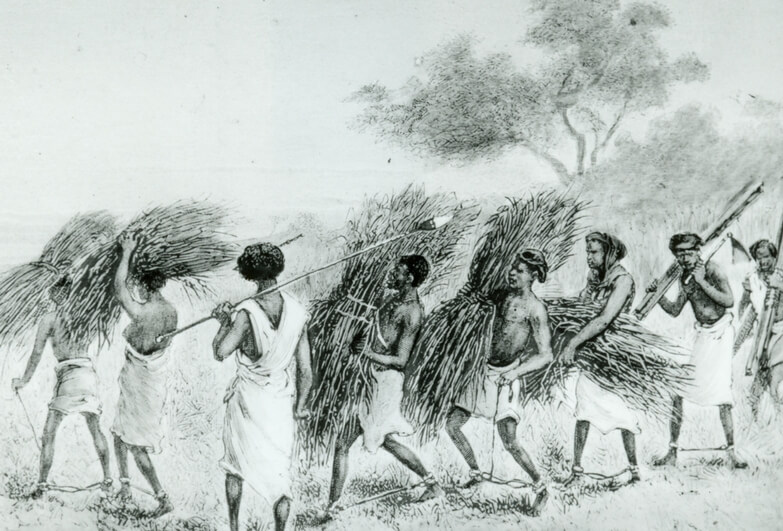

From a simple factual angle, a focus on 1619 is obfuscating and minimises African agency during the preceding century. Three moments in time illustrate this clearly. Africans were labouring in the English Atlantic colony of Bermuda in already May 1616. Evidence also suggests that Francis Drake arrived at Roanoke Island in 1586 with a number of enslaved Africans he had seized from Spanish vessels.

Yet earlier still, a Spanish-led invasion of present-day South Carolina from Florida in 1526 included enslaved Africans. Later, these same Africans rebelled and destroyed for all intents and purposes the Spanish capacity to sustain their would-be colony. Almost 100 years before the Jamestown barter and sale of enslaved Africans, fiercely resistant African peoples crippled a European colonial misadventure.

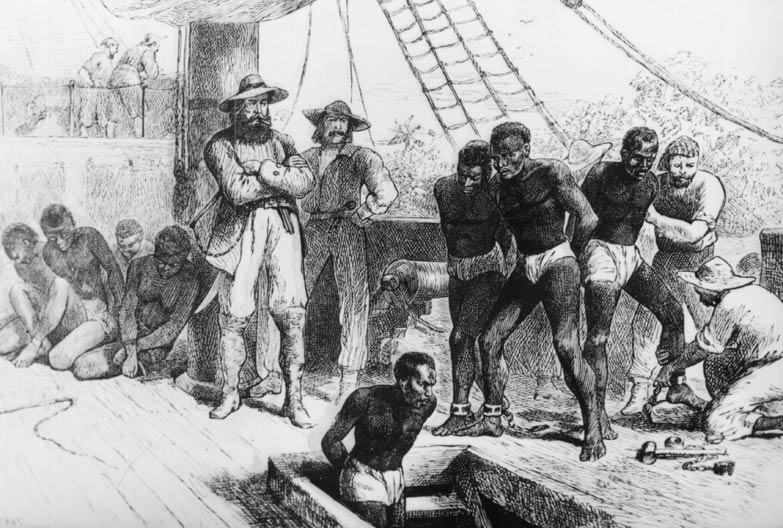

England was indeed already heavily engaged in the slave trade, and long before Jamestown. If slavery is made to begin in English America in 1619, what happens to the English slave traders who operated prior to this date? John Hampton, Thomas Hawkins, and Thomas Bolton, all from Plymouth, made multiple voyages from English ports to Sierra Leone and then to ports in Spanish American colonies, likely profiting handsomely. The income generated by 1709 slaves bought in Sierra Leonean ports and 1410 survivors sold in Spanish America filtered throughout the English Atlantic economy. The African survivors of those voyages were dispersed to slave-holding plantations throughout the region, and many would have interacted with English colonisers.

The focus on 1619, however, results in a third grander occlusion that is much more troubling. When we focus on Virginia and the Chesapeake region, we overlook the 466,629 Africans who were forcibly embarked in slave ships from Africa between 1514 and 1619. That number alone is greater than the entire number of enslaved Africans who arrived in the United States. We overlook the 372,924 who arrived alive in the western hemisphere, and the approximately 18% or 93,705 who died in horrific conditions in the Middle Passage.

Ultimately, a focus on 1619 whitens and Europeanises the history of North America. White Christian Europeans are yet further entrenched at the centre of US history. 1619 centres Europeans and exceptionalises Africans. But most troubling, it erases the Algonquian peoples – one of the most populous and widespread North American native language groups. In 1619 the majority of Virginians spoke Powhatan and related languages, and the land was occupied, farmed, and hunted by Mattaponi, Nansemond, Chickahominy, Pamunkey, Renape and Patawomeck nations and others. And the land was not called Virginia, it was Tsenacommacah.

The focus on this anniversary is yet another example of Europe-centric viewpoint taking hold of the narrative of our history. It should also serve as a lesson for today’s abolitionists, so that our “Western” perspective doesn’t dominate the work against slavery in its contemporary forms still existing across the world today.

180 years of fighting slavery

180 years of fighting slavery