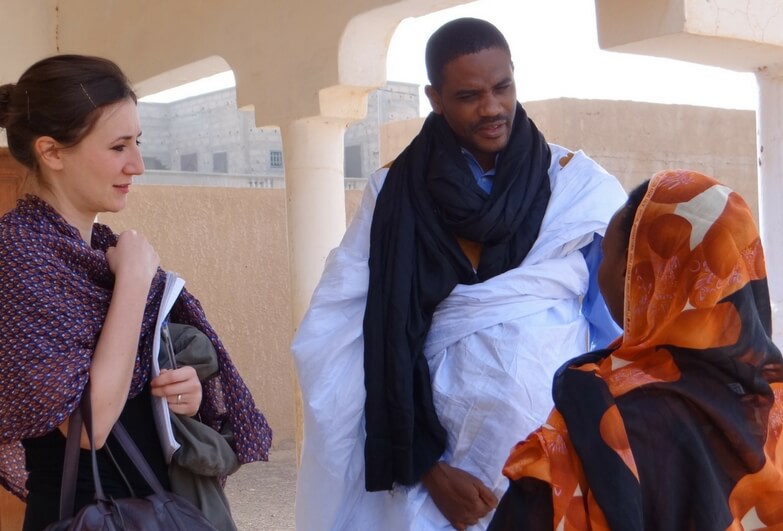

Sarah Mathewson, Africa Programme Co-ordinator, analyses how widespread discrimination against women makes them extra vulnerable to exploitation and slavery, based on the West Africa example.

8 March 2016

Looking at the forms of modern slavery all over the world we see that women and girls are not only more likely to be exposed to slavery but that they face greater difficulties in leaving slavery, due to pervasive discrimination against them because they are female.

In systems of descent-based slavery in West Africa, both men and women are treated as property from birth and are subjected to a life of forced labour. Yet the experiences of men and women are often different.

Girls and women are routinely subjected to sexual abuse and rape by masters. Any children they bear are also considered slaves, and as such, women are an important and valuable resource for new slaves. This means that girls and women are usually given duties in the domestic sphere, in order to restrict their movements and social interactions. This serves to prevent their escape or other threats to the sexual and reproductive control of masters. Because women have dependant children, it is often far harder for them to escape slavery, and to provide for themselves and their dependants outside of slavery.

Throughout human history, male dominance and control over women has been sought, exercised and celebrated. We see discrimination in favour of men in every country in the world, including our own, whether it’s in unequal pay for the same work, or women’s testimony being held as less credible, or the ‘feminization’ of poverty, with women relegated to low-paid menial labour, or work that is undervalued because it is seen as ‘women’s work’.

Most countries’ legal and cultural institutions explicitly or implicitly privilege men, giving men control even over women’s bodies and reproductive capacity. In many countries male violence against women is not criminalised. This is the case in Mauritania, in West Africa, where marital rape is also not a crime. According to the 2001 Family Code, women remain perpetual minors in the eyes of the law. They have the same legal status as children. A culture of control over women can certainly facilitate the treatment of women as property.

Gender stereotypes may also reinforce the dynamics of slavery, as notions of subservience and docility are typically held as inherent to femininity, while authority and aggression are fundamental to masculinity. And childcare and domestic labour have long been regarded as part of women’s ‘natural’ function, rather than work that should be offered with decent pay and conditions.

Patriarchal culture supports and favours the exercise of ownership over women – and the exercise of ownership over a human being legally constitutes slavery. There are many other factors that make people vulnerable to being treated as property, like belonging to any socially disadvantaged and oppressed group, but typically being a woman has a great deal to do with vulnerability to situations of slavery.

Inequality between the sexes can also decrease the likelihood of escape or redress from slavery. For example, in Mauritania, men from the slave-owning classes dominate the judiciary and police, and with strong interests in maintaining the system, delays and failures to follow due process are commonplace. Furthermore, as women escaping slavery are extremely disempowered by the law, and are usually destitute and illiterate, they are often too intimidated to pursue cases in courts.

We even have to contend with the issue of sexism within anti-slavery movement itself. Many men of slave descent join the anti-slavery movement because their power has been undermined and threatened by the discrimination they face. But often the power they seek to reclaim includes power over women. I have heard many men describe the condition of enslaved men by saying: ‘he wasn’t allowed to own anything – not even his own wife!’ or ‘he didn’t even have authority over women!’

Anti-Slavery International has introduced training on gender and equality of the sexes in many projects, but sometimes there is a lack of genuine engagement on the part of male participants. They may feel that women’s calls for equality are secondary to the ‘real’ cause of ending the slavery, or even that relinquishing power to women undermines their power further.

Having said that, we do also work with many incredibly inspiring women leaders and women who have overcome the odds stacked against them. Organizations led by men may be better known or be given more of a voice in the political arena, but it’s really important to us that we recognize biases in favour of men and take positive action in favour of women.

We at Anti-Slavery recognise women’s unique vulnerability to exploitation and slavery, that’s why last year we opened the new Women and Girls Programme to target those vulnerabilities. In my own West Africa work women’s rights and liberation are extremely high on the agenda, including opening a special project in Mauritania targeting support specifically for women and girls coming out of slavery.

We see this focus as part of a broader effort to promote the liberation and full equality of women all over the world.